The underlying basis for all of transfusion, transplantation and ART is the voluntary donation with consent of the donor or donor’s family. Without the generosity of this altruistic effort, transplantation would not have been able to provide the medical care that has been developed over the last century. In the context of organ shortage, the importance of protecting donors and potential donors, particularly in vulnerable groups, has been highlighted in a number of international reports on the subject of trafficking or organs, tissues and cells (5), (6). Regularly scandals involving the trafficking of human beings for the procurement of organs or the sale and purchase of organs and tissues from the deceased are shocking the public and challenging its trust in donation and transplantation services. National boundaries are no obstacle to unscrupulous individuals motivated by profit and seeking to take advantage of vulnerable poor populations in low and middle income countries (7). Medical products of human origin circulate across national boundaries for good and bad reasons. In addition to importation of organs and tissues, patients are traveling between countries to receive transplants (i.e., transplant tourism) and thus the risk of importing new diseases in the immune-suppressed recipients is amplified. During 2005, a report from the state of New York in the U.S. identified a serious problem with donor recovery being undertaken outside of all standards and regulations. An organization was discovered to be recovering donors from funeral homes without the permission of families, without adequate medical screening, and was, in many cases, falsifying records. Tissue was sold to a number of processing centers and distributed both nationally and internationally.

Noting the global increase in allogeneic transplantation of cells, tissues and organs, the World Health Assembly Resolution WHA57.18 in 2004, urged member states:

1. To implement effective national oversight of procurement, processing and transplantation of human cells, tissues and organs, including ensuring accountability for human material for transplantation and traceability;

2. To cooperate in the formulation of recommendations and guidelines to harmonize global practices in the procurement, processing and transplantation of human cells, tissues and organs, including development of minimum criteria for suitability of donors of tissues and cells;

3. To consider setting up ethics commissions to ensure the ethics of cell, tissue and organ transplantation;

4. To extend the use of living kidney donations when possible, in addition to donations from deceased donors;

5. To take measures to protect the poorest and vulnerable groups from “transplant tourism” and the sale of tissues and organs, including attention to the wider problem of international trafficking in human tissues and organs in 2006

(8).

The WHO Guiding Principles on Transplantation, adopted by WHA Resolution 63.22 in 2010 reiterated the need for all stakeholders to ensure that donors are not exploited or human substances commercialized.

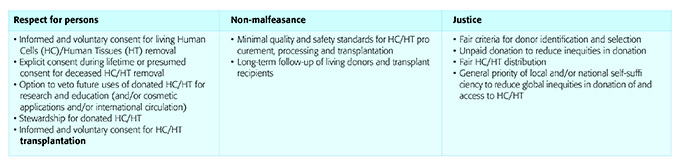

An international consultation in Zurich in 2007 addressed perspectives on the ethics of human cell and tissue transplantation and arrived at a number of consensuses in 2007

(9). Consensus included (Table 1):

Donors of blood, organs, tissues and cells should not be exploited and the health risks associated with donation should be thoroughly explained and minimized. The following sections summarize these risks for the donation of different types of human substance.

To put an end to trafficking and exploitation of donors and recipient the best solution is to meet the needs of all patients in need and reach self-sufficiency by building efficient services for the donation and clinical application of medical products of human origin. Self-sufficiency can be defined as meeting the needs of patients from a given population with an adequate provision of transfusion and transplantation services and supply of organs from that population. The self-sufficiency paradigm, as defined for organ during the Third WHO Global Consultation on Organ Donation and Transplantation (Madrid, 23–25 March 2010) applies to any MPHO.

With government support and oversight, the paradigm underwrites:

• Equity in donation from possible donors and equity in allocation

• Education about donation but also about prevention of conditions that create a need for MPHO

• Transparency and professionalism

For example, striving towards self-sufficiency requires comprehensive management of chronic kidney disease, from prevention to renal replacement. Likewise, the national organ donation and transplantation service must provide the opportunity to donate organs after death in as many circumstances as possible.

In accordance with WHO (

http://www.who.int/bloodsafety/voluntary_donation/en/) blood transfusion safety is based on voluntary, non-remunerated blood donors from low-risk populations. In the key global fact and figures in 2011 (Fact sheet number 279, in 62 countries, national blood supplies are based on 100% or almost 100% (more than 99.9%) voluntary unpaid blood donations. Forty countries collect less than 25% of their blood supplies from voluntary unpaid blood donors. The WHO goal is for all countries to obtain all blood supplies from voluntary unpaid donors by 2020 in accordance with World Health Assembly resolution 28.72, which was adopted in 1975.